Intermediate Level

Close-in Fighting

The tournament style martial arts-mentality teaches that for a smaller person to win or to be competitive they must fight “close-in.”[1] In theory I do not disagree with this assumption, but this close-in philosophy assumes that you are already a skilled fighter. Many contemporary authors and knife fighting instructors advocate this “close-in” strategy. You should question whether this is because it will work for the average guy or gal on the street, or because these instructors are highly skilled and it works for them? Fighting close-in with knives might be compared to rolling around in a barrel of splintered glass. No matter which way you turn you are going to get cut! With this analogy in mind you will appreciate why I personally do not advocate close-in fighting. As a reminder, this book is written specifically for the untrained, smaller, weaker person, and for women, all of whom are too often the targets of criminals and who are ill suited for close-in fighting.

Coming to Grips

You may only have one chance to disarm or defeat your attacker without suffering serious personal injury or loss of life. Your chances for success hinge upon your composure, awareness, and timing. Almost without exception the direction of an attack can be predicted by observing which of the four following grips the attacker is using. “Almost” is the key word here. A skilled knife-fighter may change his grip in mid-attack or change his angle of attack during mid-stroke. A completely unskilled person may use the knife in totally unpredictable and illogical ways. An attacker, no matter how skilled, will probably start out using simple moves, assuming you are easy prey.

The Ice Pick Grip

The Ice Pick GripThe most elementary grip, the one often used in horror flicks, is the theatrical “Ice Pick” grip. Ironically a slight variation of this called the reverse grip, is the hallmark of a highly skilled knife-fighter. The ice-pick grip, commonly ridiculed by “professional” knife fighters, provides very powerful overhand strikes. Knife strikes of this type were used during the Middle Ages to penetrate a knight’s heavy armor for the coup de’ grace.[2] When held in this grip the knife can also deliver very powerful slashes. Fortunately for the defender these strikes and slashes are quite limited in range of motion and probably the most easily avoided by using simple diagonal stepping.

Probable attack #1: Overhead Stab

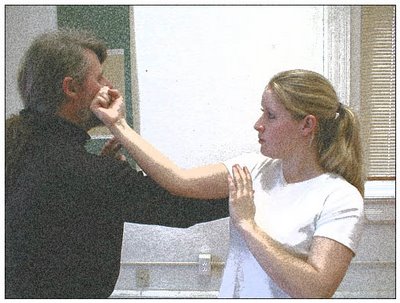

It is very important that you move off center, out from under any overhead strikes rather than trying to block them! As mentioned before, these strikes can quite easily break through most karate forearm, or “X” cross blocks, with predictably dire results. Your best move is to step out to your left with your left foot (the attacker’s right side) and redirect the attacker’s strike (3) by using his own energy to guide his arm in a natural arc, driving his knife into his own leg or groin area (4).

Shown here (4) is the termination of the overhead stab as it is guided by the defender into the attacker’s own leg. She is using a soft circular movement that relies on the attacker’s own energy for his undoing.

Ma-ai: Small Word, Big Concept

My studies in karate and kenjutsu have provided me with certain Japanese phrases that I prefer to use to explain certain martial arts concepts. For the reader remembering the words is not important, but learning their meaning is very important.

My studies in karate and kenjutsu have provided me with certain Japanese phrases that I prefer to use to explain certain martial arts concepts. For the reader remembering the words is not important, but learning their meaning is very important.The first of these concepts I want to discuss is

Ma-ai. Ma-ai is an excellent example of the multiple layered definitions these terms possess. Ma-ai is a Japanese word that roughly translates as “distance”. Remember what I said about keeping a safe distance in the section on awareness? Ma-ai is not a distance measurable in feet or inches, but distance relative to combative engagement. Ma-ai is also one aspect related to the mystical circle or octagon that European rapier duelists studied. I will discuss the octagon in greater detail in the advanced section of the book.

Partially defined, ma-ai is the span from which a successful attack can be launched or rebuffed. These two distances, defending and attacking, may or may not be identical. The distance of engagement is determined by a number of things.

Hollowing out; a bad technique

Like the “Filipino Grip”, there is another technique whose use I completely disagree with. At least one well known self-defense instructor relies heavily on a technique called “hollowing out”. I do not doubt his personal abilities, but I do not approve of this technique! Hollowing out (16) is where you suck in your stomach and bend deeply at the waist to give yourself a “safe” margin against a thrust or slash. I am sure that even the most lethargic of attackers can out-maneuver your hollowed-out, backwards-stumbling figure. This is an example of one of the worst instinctual moves that can occur when you have nothing else to rely on.

Let us assume for a moment that you are the one with the knife, and that you initiate a strike or cut and your attacker performs a block (23). Your natural response is to retract your arm and try again but if the attacker checks your arm you are in trouble. Passing with a weapon provides you with the means of continuing your attack.

Since we are discussing methods of stepping let us consider leg sweeps. Leg Sweeps (30a,b,c) are techniques usually reserved for the trained martial artist. Using the outside line sets you up so perfectly for a sweep that I hate to pass it by. Believe me you can do this with very little practice! Leg sweeps are blindingly fast techniques.

To Aggress or not

Every writer and instructor has a differing opinion on whether you as the defender should, or should not, initiate the action when threatened. We talked about making these choices in the very early chapters of the book. My advice to you is again based upon the philosophy of the 16th century Yagyu Shinkage Ryu teachings. (By the way, if you are wondering whether four-hundred-year old sword techniques and philosophy are suitable for modern knife work or defense, trust me, they are!) Good techniques are timeless, that is why they have survived to this day and continue to be taught. The only effect the length of a weapon has on strategy is slightly altering the timing, speed, and obviously the distancing.

· One: Your aggressor may take your calm demeanor as a sign of confidence and skill and back off.

· Two: When either person attacks they have committed to a line of motion. If you have waited the options are now yours, of parrying, counter-attacking or just backing off. You have the advantage of knowing what they are doing; they have to guess at your response.

· Two: When either person attacks they have committed to a line of motion. If you have waited the options are now yours, of parrying, counter-attacking or just backing off. You have the advantage of knowing what they are doing; they have to guess at your response.

When discussing the choice between aggressing or waiting we inevitably come to the notion of providing a secure defense. Centuries ago it was discovered that every castle should be purposely built with a “weak” spot. Eventually those laying siege will “discover” this weak spot, which you of course have set as a trap. The understanding of leaving a gap (suki) must be learned through actual training.

Killing Snakes

The tactic of beating the grass can be used to startle your opponent causing him to attack. For example, you feint, the attacker responds, but he aborts his response when he realizes it is a feint. Then as the opponent withdraws his counter attack you follow him in, without any hesitation, with your originally intended attack. This is called a double feint in some schools. Timing is critical with this technique! As I mentioned before, one notable knife instructor advises: “Watch the hands it’s the hands that will kill you!”[4] Watch them too closely and they just might. Remember to use peripheral vision and watch your attacker’s shoulders or the center of the chest. Any hand movement will be naturally detected.

I did not set out to teach knife fighting in this book but I have decided to explain a few of the techniques knife-fighters use. It is obvious that familiarity with the art of knife fighting will give you deeper insights into defense against the knife and vice versa.

One basic knife technique is the “snap cut”. A snap cut (35) is a very quick, reflexive, whipping cut that uses speed more than power. A snap cut may use either the tip of the knife or the full length of the edge. The desired result is not a conclusive, death-dealing blow, but a quick, bold cut that will distract, disable and hopefully disarm your attacker. Snap cuts are usually targeted at the hands and the tendons of the wrist.

De-fanging the snake may also be performed empty handed without the benefit of a knife. The best method is to direct a strike to the tendons on the back of the attacker’s knife hand using a kubotan, closed folding knife (36), or the butt of a fixed blade knife. Always remember that in this way a knife may be used in a non-lethal capacity.

De-fanging the snake may also be performed empty handed without the benefit of a knife. The best method is to direct a strike to the tendons on the back of the attacker’s knife hand using a kubotan, closed folding knife (36), or the butt of a fixed blade knife. Always remember that in this way a knife may be used in a non-lethal capacity. [1] “Close-in” means that you may strike, or be struck, without you or your attacker taking any steps.

[2] The finishing stroke ending the life of the defeated combatant in mortal combat.

[3] Echanis, Michael. Knife Fighting, Throwing for Combat. Burbank: O’Hara Publishing, 1978.

[4] Hockheim, Hoch. “Counters to Knife Quick Draws.” Close Quarter Combat. July 2001: 23.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home